In my fantasy version, I travel back along the matrilineal line, and convince that first aberrant cell to pick on someone its own size. To grow without such cowboyism. To leave my mother alone.

When I was 12, I had my first mole removed from my back, close to my lumbar spine, in a zone of vulnerability. It was “irregular”-- something you don’t want your moles to be.

The swaggering dermatologist told me that I was lucky— during the civil war they did this procedure without anaesthesia. With a swig of whiskey at best.

You know, all those moles removed in the 1800’s, threats to the Union!

This dermo had no pediatric whiskey, nor bedside manner, nor ability to imagine the world view of a tween. His anaesthesia needle was long and terrifying and he showed it to me proudly before inserting it. I was face down on his table, so my wild imagination had nothing to do but nod along. It was the 1990’s, when we had advancements. Mail, and bad news, was no longer delivered by donkeys.

My mole was also “Pre-cancerous.” It’s like saying “you have lots of potential!” In a bad way.

My overprotective dad was with me. Parents can’t make everything better. After the procedure, the doctor showed us the excised tissue floating in alcohol in a jar like a miniature jellyfish. It was beautiful in an awful way, and when we left, I thought maybe it followed us, a forlorn evicted specimen. In a sense, it did.

The scar healed poorly, due to spinal flexion— since the spine is built to flex, surely the dermatologist could not have anticipated this strain on his sewing! There was a puffy pink blot where my dark mole had been. A bite out of the moon. Still, it was better than the future cancer could have written.

My generous parents gave us a dermal legacy of basal cell clusters, benign skin cancer that begs frequent removal. Most often from one’s face. Our skin apparently loves personal growth. Lots of it.

2 years ago a deep basal cell carcinoma, caught and biopsied in an annual screening, was removed from my forehead. The skilled surgeon numbed the area with a vibrator— yes, that kind— before giving anaesthesia, letting me choose the playlist for the Moh’s surgery. Its journey toward bone arrested, I was again a mother and not a tragedy, but graduated into qualification for more frequent full-body checks. Have you had yours?

Last year, very pregnant and worrying about the future, I brought my 8 year-old to have a few of his own large moles examined. Ro could barely look up from his fat apocalyptic novel as I showed the doctor his irregularities, which were all Benign. They traded fantasy book recommendations. He wished me luck with my birth, and we left. When I had the baby, she, like my other babies, picked at my moles to soothe herself.

In my fantasy version, I can similarly pick off, pluck at, whatever has the potential to kill my mother. Trade a nominal discomfort for a much more terrible one.

A melanoma survivor, my mom was militant about getting her full body mole screenings done multiple times each year by an expert (who left the field to manage her own breast cancer), and reminded me to do the same. She recommended I take arnica to minimize the post-surgical bruising. She was a candidate for a new laser surgery for her most recent basal cell on her nose, when history turned. Instead, mom spent the winter dying of aggressive adenocarcinoma. Sometimes you are looking meticulously in the wrong place.

Researching as one shouldn’t, I’d found a possible tenuous etiology, something about multiple melanomas going underground and invading deep abdominal organs. I wanted to float this possibility for the expert oncologist. Leave it to a writer to find a novel origin story. But he never brought up causes. We were beyond the need to know them.

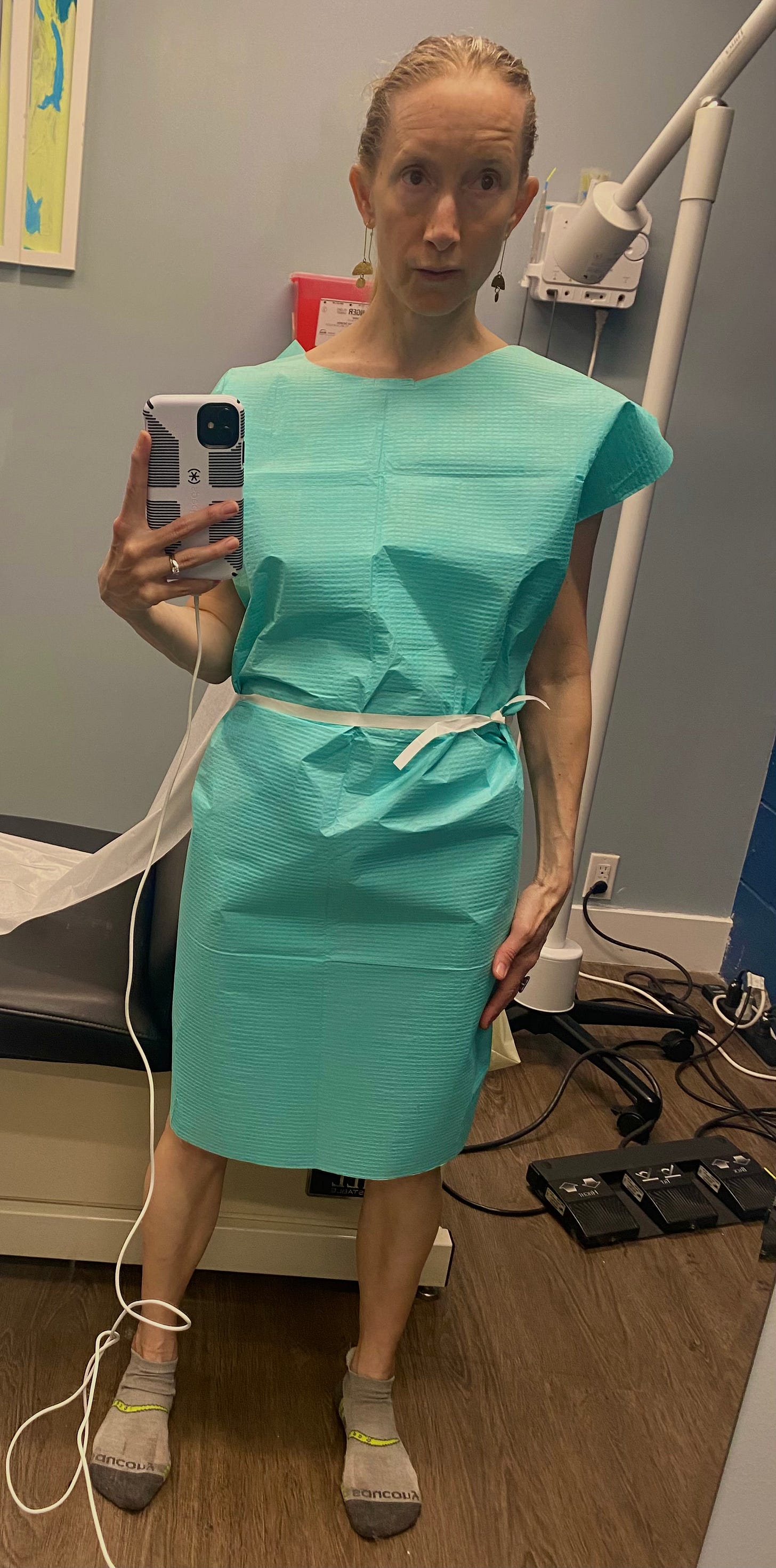

This past weekend, 9 months postpartum with my third bio baby, and in the first stunned weeks of mourning, I finally went for my yearly dermatology scan, which I’d delayed, serially rescheduling. Pregnancy had made my skin be fruitful and multiply- the mole, the merrier. But then my mom’s escalating illness- and my mom, period— had become more important than anything.

The dermo declared my moles all clear, and me in good (skin) health. He used a magnifying glass, sifted through my hair, so surely no problems could be undetected. Still, I was hardly convinced that meant I was off the hook.

What if all reassurance is similarly false or fleeting, but we seek it anyway, needing to know we are safe in at least one category? At a reasonable distance to avoid a jellyfish sting, a whale eats us. Even temporarily trusting the “OK” is not easy after the con of her late stage pancreatic diagnosis, but I try. Wondering what makes any of us feel we are OK, ever.

After the exam, I threw out the paper cocktail gown, and got dressed. My mother had been so freezing cold in the rooms where her final internal scans were done. It took it all out of her, to be checked in on. In my fantasy, which I’ve fucking downgraded, they at least give her some warm ginger tea to offset the frigid machinery.

Mired in a cellular civil war, she texted me anyway to remind me to be sure to get my annual mole screening. To ask me if I’d scheduled yet (No). How lucky I was, to have a mother who wanted, above all, for us to identify the suffering we could stave off, and cut ourselves free of it.